Stick around for joy

This post is about music and how we consume it. It delves into what's changed in the widespread transition to digital audio formats over the last couple of decades.

It’s also about technological progress, the unquestionable benefits it's ushered in, and what we stand to lose.

When the game is up

Since 2008 I’ve moved house six times, and each time I’ve hauled several cardboard boxes packed full of compact discs around with me.

In our current family abode, the boxes have languished in a storage cupboard since 2016. I’ve occasionally opened them, peeked in, grabbed one or two CDs to reminisce, but rarely listened to any.

Since my old Sony Boombox (“vintage”) gave up the ghost about ten years ago, there’s not even been a dedicated device to play CDs on.

Consequently the boxes have gathered dust and become little more than obstructions we all clamber over while searching through the cupboard.

So with a heavy heart it’s time to admit that – in our household at least – CDs are now obsolete, defunct, a much-loved remnant of the past.

I am what I listen to

My CDs were last on show in a little flat I owned in Oxford, where they occupied a disproportionately large amount of the living room.

The display case they resided in featured music I liked, music I loved, music I tolerated, guilty pleasures, Kylie.

Sometimes alphbetised, sometimes colour coded (sorry Marina Hyde), sometimes randomised, always pride of place.

More so than books, CDs reflected my sense of self. If people visited, I wanted them to look, to flick through, to stick one on. Similarly if I visited someone else’s house, flat, or student digs I’d look for the not-so-subtle clues that we might find a bond over musical interests.

Dummy, Different Class, Maxinquaye, Dog Man Star, Moon Safari, even the goddam Trainspotting soundtrack – music that was era-defining and near omnipresent at a particular points in my life.

CDs were a conversation starter, and sometimes a friendship builder.

A selective history of streaming

I won a Rio 600 MP3 audio player when I entered a competition in Q Magazine at the turn of the century.

It was clunky, sucked batteries for breakfast, and could store about 16 tracks on a good day. It also required a degree in engineering/patience of a saint to transfer tracks onto.

However its lack of moving parts and the ease by which I could carry it made it instantly preferable to a wobbly old CD Walkman; you could sniff change in the air.

In common with much of the mainstream technology we [ahem] know and love, it took Apple to get in on the act and truly shift the dial.

When the first iPod was released in 2001, it ushered in an age of properly mobile music ("1000 songs in your pocket"), random shuffling, and the mass digitisation of all previous storage formats.

I loved all three of the iPods I owned – the big chunky black one, the long thin red one, the petite square silver one. Effortless and accessible, and still full of my tracks, it became the digitised companion to all those physical CDs without taking up shelf room.

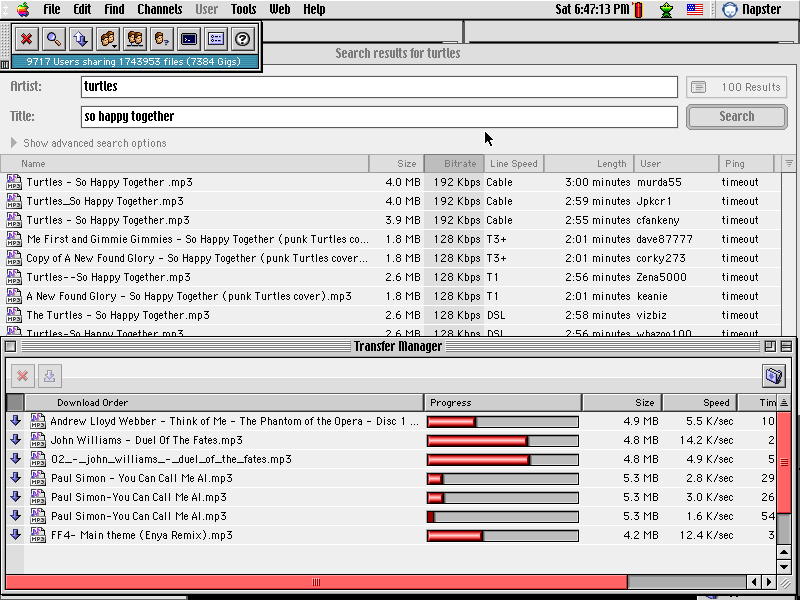

At the same time as the iPod's release, streaming was beginning to make an impression. The initial wave mostly passed me by: I was certainly aware of Napster but it was favoured by people who were comfortable with an unweildy user interface and misspelled song titles. 👇

It's intriguing to look back at the hugely controversial, and highly consequential, battle between Naptser and Metallica. At the time, the story was often pitched as a David v Goliath clash between a plucky young tech start-up and entitled rock dinosaurs – these days it's not so easy to work out who the goodies and baddies are.

Napster’s heyday came at a time when the portability of files was limited. Before smartphones, streaming was very much a desktop experience, tethering your songs to whatever networked computer you happened to possess.

It's no coincidence that when the iPhone and Spotify first emerged, in 2007 and 2008 respectively, the availability of audio on the move was a defining selling point of both products.

And that's foreshadowed an almost incomprehensibly huge step change in a relatively short space of time: the transition from me picking a CD off a shelf and listening to it from the confines of a solitary bedroom in the 1990s, to the option of tuning into practically any audio, anywhere, at any time, is enough to make your head spin.

Tainted tech

From the get go I was a full-on Spotify fan boy. It instantly flipped me into the era of streaming – early adoption led on to a paid subscription as soon as it was first available.

When I first discovered the smörgåsbord of music and songs, later followed by personalised recommendations and playlists, it felt like everything I'd ever wanted from a service.

To my mind, at the time, this was the natural order of things – the world was going digital with a move to accessible, shareable formats and the ability to unearth new artists and genres without limits.

Alas, limits there are. And as with so many technology tales, there’s a sting. 🦂

I first wrote about my Spotify reservations in a post back in 2023. It was largely a Joe Rogan inspired rant (thankfully he's vanished off the scene now, eh?) which also probed around other morally-ambiguous areas, such as Daniel Ek – Spotify's CEO – funding and co-chairing a company that creates "AI-enabled electronic warfare capabilities". 🤔

The main controversy that tends to dog Spotify is the fact it pays some of the lowest artist royalties of all streaming platforms. Now they appear to be notching it up a gear with steps to squeeze artists out altogether.

Liz Pelly’s superlative essay in January's Harper’s Magazine documents how Spotify is gently nudging industrially generated music into our playlists. It's a long, fascinating read (itself an excerpt from Pelly's forthcoming book Mood Machine, due to be published in the UK in March) which details how the 'Perfect Fit Content' program seeks to profiteer.

Perhaps in isolation this doesn't seem like a big deal? If you’re looking for some ambient chill as a backdrop to your day, maybe it doesn’t matter if a nameless artist and clever algorithm has come up with the sequence you’re listening to.

But it’s the thin end of the wedge. Wringing cost out of the system has been part of Spotify's playbook since inception: musicians need to be paid + royalty fees are expensive = find innovative ways to undercut.

Spotify has long tinkered with AI tools and widgets so it's far from inconceivable that the further removal of humans from the loop is all part of the game plan.

As Pelly puts it:

A model in which the imperative is simply to keep listeners around, whether they’re paying attention or not, distorts our very understanding of music’s purpose.

How desperate have things got if we're removing musicians themselves from the creation of music?

Bottom lines, bottom feeders

I'm very aware that my posts lean towards a somewhat naive bleeding-heart liberal view of the world. Whether it's Meta, or Substack, or X, or the pumping of AI in general, I've written * a lot * of words that cock a snook at how dominant technology players and platforms behave.

I guess my perspective is that as consumers, we always have choices. Technology makes this difficult – supply chains are complex, the relationship between different services is opaque, it's hard impossible to be squeaky clean. However we can consciously endeavour to do less harm.

Spotify fits into my own "do less harm" category. There are multiple services that offer up the same catalogues of music, podcasts and audiobooks. None are perfect, and none will provide up-and-coming musicians a decent wage (still gotta go to gigs, buy merch, sign up to mailing lists) but their activities don't seem quite so nakedly capitalistic.

Since abandoning my Spotify premium account three years ago, it's made little difference to my listening patterns. Playlists are portable, other services come bundled with better quality audio, most pay artists more, not everyone is lobbying the EU in flagrant self interest. I can absolutely get by without an AI DJ.

In the inimitable words of Björk:

“...Spotify is probably the worst thing that has happened to musicians. The streaming culture has changed an entire society and an entire generation of artists.”

And speaking of Björk...

For sale: many CDs, fairly worn

So what to do with those boxes of compact discs? Charity shops are getting much more discerning, options for recycling are limited, you can only scare so many birds.

I searched online and found a few different services that buy second-hand CDs only to discover that most simply didn't want my precious music collection. 😢

After a bit of trawling, Music Magpie came up trumps, with a much higher hit rate than similar services [incidentally their end-to-end service is excellent: an app that scans barcodes super quickly; a choice of postage options; a quick QR code scan at the Post Office; regular and informative emails].

It's all relative though: I sold just shy of 250 CDs (original retail value approx. £3,000) for the princely sum of £47.52.

I decided to hold on to a few. I kept all of Pet Shop Boys CDs, and I picked out a selection of discs that meant something to me musically, or because they represented a specific time or place in life.

Björk features prominently, and the name of this post is an homage to how a performance on Top of the Pops could alter a teenager's listening habits for life.

The mere act of sorting through the CDs was a lovely way of stepping back in time. I spent several hours over several days sifting, fixing broken cases, and streaming songs I hadn't heard in years. Never underestimate the power of a physical object to trigger a memory, conjure up long-forgotten feelings, or spark off a story.

Y'won't get that from no automated playlist.

Further listening:

- Liz Pelly's interview on the Tech Won't Save Us podcast

- Feature on the latest Hard Fork podcast

💿 Thank you for reading.

Member discussion